Originally posted to Substack.

Special thanks to Michael Jordan and Joe Coll for their review.

Introduction

Despite the title, you’ll be hard pressed to find someone more excited about Ethereum than myself. However, I believe the narrative and policy objectives around ETH the asset are in need of some refinement. It appears to be a pretty contentious issue based on my very scientific polling:

This is the first of several upcoming pieces on my framework for ETH. I’ll cover the basics here:

- How value flows through the Ethereum protocol

- What ETH is exactly, and why it matters

- Why you’re probably wrong about blockchain “profitability”

Future pieces will go much deeper:

- Comprehensive look at traditional assets, economics, and monetary policy to understand how crypto-assets fit in

- How stablecoins will factor into the evolving crypto-economy

- How ETH’s role may evolve in a rapidly changing tech stack (e.g., adding a DA layer, execution layer upgrades, users shifting to rollups, proliferation of LSTs, re-staking, etc.)

- What changes we may consider to Ethereum’s economic policy

- Why deflation doesn’t make ETH “ultrasound money”

- Can ETH actually become “money,” and should it even try to be?

Additionally, I recently shared a simple Ethereum model linked below. Playing with the assumptions helps to provide an intuitive sense for how Ethereum’s economic engine operates and how it will change.

This is a detailed functional Ethereum model including long-term roadmap items

Flexible to easily run any scenarios/timing (eg, when 4844, danksharding, rollup data compression rates, staking rates, fees, MEV burn, issuance, etc)https://t.co/iMBzdbJi8M

— Jon Charbonneau (@jon_charb) January 29, 2023

ETH’s Value Flows

The primary components are transaction fees, other MEV, and issuance.

Transaction Fees

EIP-1559

EIP-1559 dictates Ethereum’s current pricing mechanism. It includes elastic block sizes targeting 50% usage on average. The current gas limit is 30mm gas per block with a target of 15mm gas. Gas is the network’s measurement of all resources.

There’s currently only one gas limit and fee market – it’s a single-dimensional EIP-1559. Whether you’re an L1 user (e.g., swapping on Uniswap) or a rollup (e.g., posting calldata to Ethereum), you’re directly competing over shared resources.

Research is underway on multi-dimensional EIP-1559 to implement different fee markets for different resources. EIP-4844 will implement the simplest version of this – a two-dimensional EIP-1559:

- Execution Layer – EIP-1559 remains as is.

- DA Layer – This will only be used to post “data blobs” (rollups will use this instead of calldata). It’ll have its own data gas limit, and its own fee market.

Each layer will have independent fee markets that float depending on the demand for their respective resources. They won’t be competing anymore, so price spikes for either layer will no longer bleed into the other.

Base Fees

The simplest fee market would just be a first-price auction (FPA) – users all bid what they’re willing to pay, and the highest bids get included. EIP-1559 instead dictates that every transaction must pay the prevailing reserve price (the “base fee”) to be included in a given block. This provides a nice UX for users:

- A public fixed reserve price makes it easy to bid for inclusion.

- A naive FPA is trickier – you’re trying to guess what other users will bid because this impacts your bid.

The base fee is deterministically calculated based on previous block sizes, changing by a max of ±12.5% per block:

- As blocks come in above 15mm gas – The base fee starts to increase exponentially to meter demand.

- As blocks come in below 15mm gas – The base fee decreases.

EIP-1559 then burns the entire base fee. This is not for the deflationary memes. Burning prevents validator + user collusion. As an example:

- The current reserve price is 100 gwei

- User is colluding with the validator, and only wants to pay 50 gwei

- The user can just bid 100 gwei, the validator includes it, then they send 50 gwei back to the user

This ability to collude would effectively remove the reserve price, reverting to a FPA again. However, the game theory does not dictate that you must burn the fee. It only dictates that the base fee must not go to the producer of that block. It would be equally incentive compatible to do something else with the base fee (e.g., pay to future block producers, fund public goods, put into a treasury, etc.).

Priority Fees

Users can also add an additional “priority fee” to get included faster.

This fee goes directly to the proposer, so they’re incentivized to include transactions with higher priority fees all else equal. However, base fees and priority fees are both “revenue” to the network. They just differ in who they benefit:

- Base fees – Benefit all ETH holders (burning proportionally increases all holders’ share of the network).

- Priority fees – Only benefit proposers.

Example

You’ll often see gas prices quoted in “gwei.” Gwei is a unit of measurement = billionth of 1 ETH. Different transactions use different fixed amounts of “gas.” The gas price then says how many gwei you’re willing to spend for each unit of gas you use. As a simple example:

- You submit a simple transaction that will use 21,000 gas

- The current base fee gas price = 45 gwei

- You want to get included quickly, so you set your priority fee = 5 gwei

- You will pay (45 gwei + 5 gwei ) x (21,000 gas) = 1,050,000 gwei = 0.00105 ETH

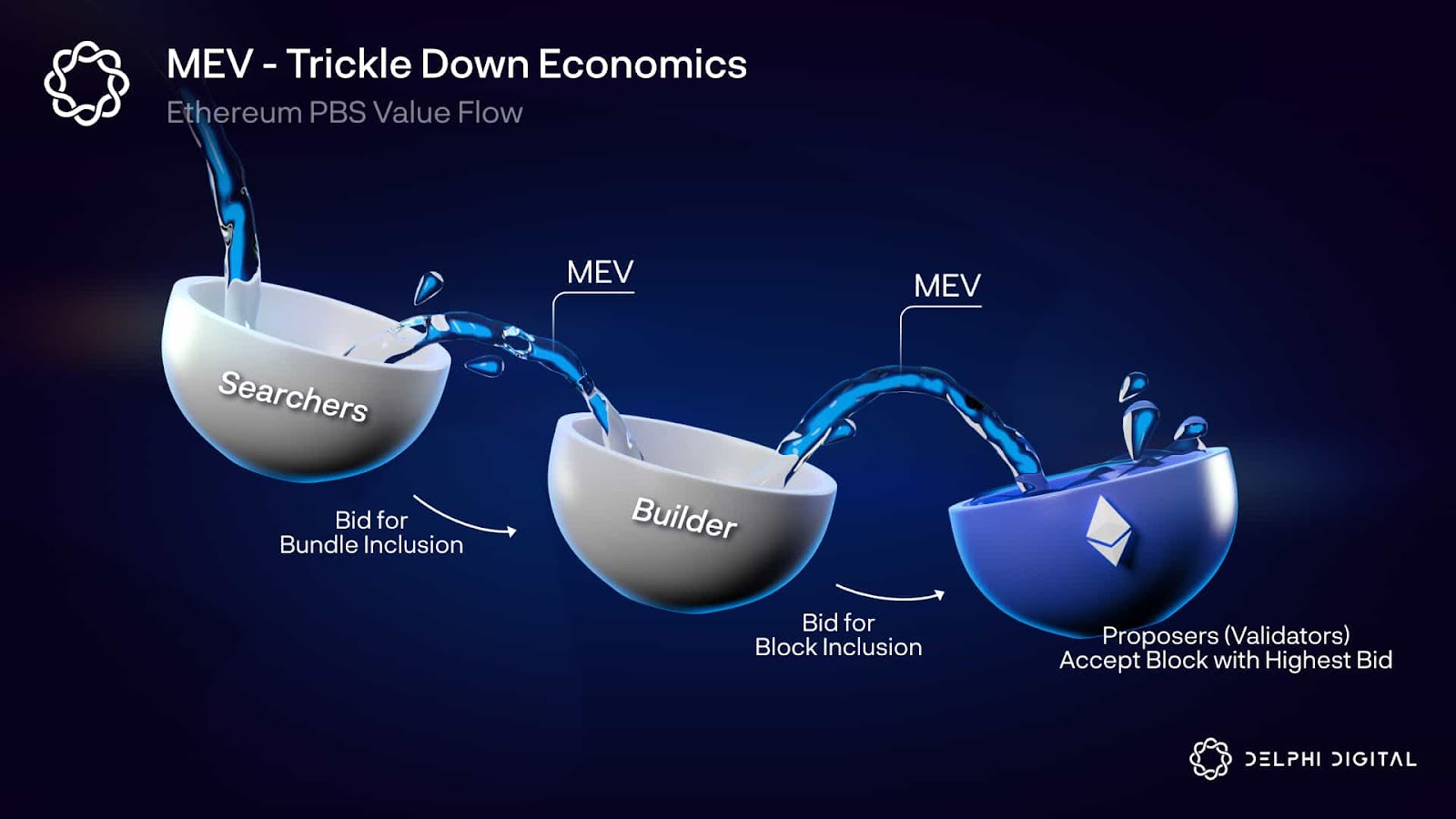

Other MEV

Validators also stand to profit from other MEV. When there’s an opportunity to pick up $100 somewhere (e.g., an arbitrage), searchers/builders should be willing to bid up to $99.99 to the validator to make sure they’re the one who gets to pick it up (in a competitive market).

Source: Me, The Complete Guide to Rollups

Note that this MEV payment to validators can be partially (but not entirely) captured under the priority fee revenue line item mentioned earlier. There are several ways to express your bid to a validator for the MEV opportunity you want to capture:

- Priority Fee – Set a high priority fee for your transaction.

- coinbase.transfer() – This smart contract function transfers ETH from the contract to the address of the validator who proposes a block. For example, the Flashbots builder treats fees through coinbase transfers in the same way they do normal transaction fees (i.e., 1 gwei of coinbase payments = 1 gwei of priority fees).

- Out-of-band – Credit card, Venmo, suitcase of cash, whatever you want. It’s impossible to know exactly what’s happening off-chain.

MEV is a bit of a wild card long-term. There are three broad areas which could change drastically.

MEV Market Size

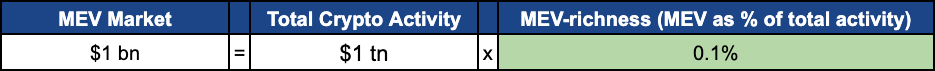

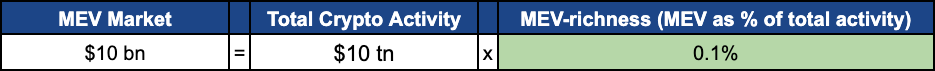

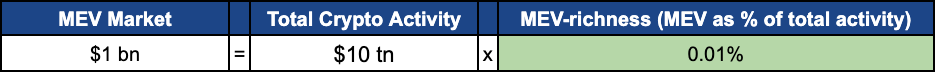

MEV opportunities exposed represent some % of total activity. Let’s assume for simplicity that we have perfect definitions and measures for total crypto activity and MEV respectively (we certainly don’t, but bear with me). Then we can define on average exactly how much MEV is exposed by activity (e.g., for every $1,000 transacted on-chain there’s a $1 MEV opportunity, so MEV = 0.1% of activity).

Then we could have this example if total crypto activity is $1 tn:

If crypto activity 10x’s:

In reality – MEV is extremely nonlinear. I’m vastly oversimplifying to highlight the variable.

This spikiness is particularly true when activity increases over short time horizons. Variations also occur with new forms of MEV and different chains’ architectures.

It’s also unclear how “MEV-rich” activity will be on a longer time scale. The composition of crypto activity is likely to change over time. Let’s say high value DEX transactions are more MEV-rich per unit of economic activity than gaming apps. Maybe this DeFi stuff goes away and crypto is just for Web 3 League of Legends (I’m not betting on it, but you get the point).

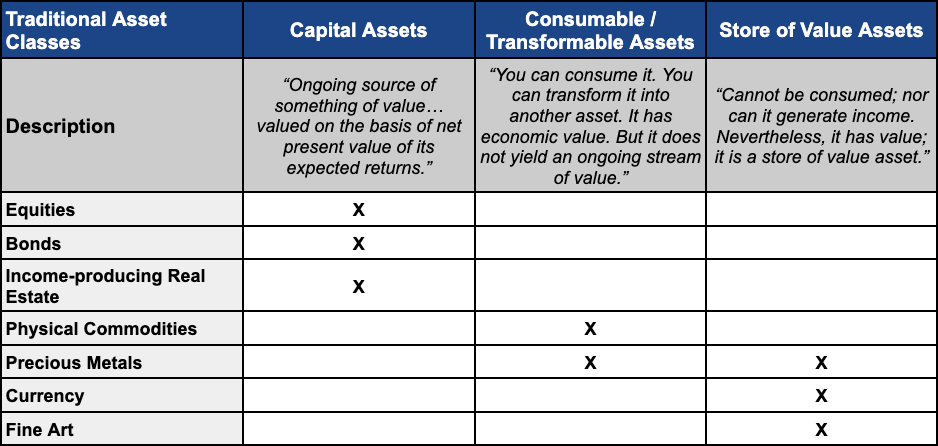

MEV Distribution

Assume you can predict the exact size of the future “MEV market.” However, the way in which that value is distributed is a huge variable. Let’s say validators capture 50% today, supply-chain middlemen (e.g., searchers, builders, etc.) capture 45%, and users get 5%. What actually matters to validators is the below:

Market size alone is clearly insufficient to predict future validator revenue. Maybe their share of the pie goes from 50% to 5% in that same time period. Now validators are flat even if the market 10x’d:

The crypto gigabrains are hard at work here – mostly trying to make sure that validators capture less of the MEV. Applications expose large amounts of MEV today, and the users don’t get much back. Protocols and apps could try to help users out:

- Expose less MEV from user transactions (e.g., encrypted mempools)

- Better assess the MEV and bid it back to users (e.g., order flow auctions, which may also incorporate encrypted mempools)

Similarly, apps and protocols want their fair cut. Those useless governance token holders want to be holding a vaguely useful governance token. Why give your MEV away for free if you can internalize it?

For example, Osmosis’ ProtoRev module is being developed by Skip Protocol to internalize arbitrage opportunities. Money that used to go to searchers could then be divvied up amongst the Osmosis LPs who are getting picked off, OSMO holders, Skip for designing and building, or however else they want. Similarly, wallets could start doing PFOF. The list goes on – it’s a big design space.

Ideally we build towards fair value attribution where:

- Users – Enough $ to get a better deal than TradFi.

- Protocols/applications – Enough $ to be incentivized to build sustainable business models.

- Validators – Enough $ to sustainably keep the chain secure.

MEV Burn

Sorry validators – forget about MEV market size and split, we’re gonna light it all on fire anyway. % of MEV to validators is now a big fat 0. MEV now benefits all ETH holders equally. That’s the proposal at least, and it’s even on Vitalik’s latest roadmap. The basic idea is:

- Today – One validator is randomly elected as the proposer of the current block, effectively giving them a “monopoly” to extract MEV for themselves.

- MEV Burn – Auction off the right to be the proposer for each block. The validator who commits to burning the most ETH in their block wins the auction. In theory, they should bid up to the full value of MEV which they can capture in the block.

I have several hesitations regarding the specific proposal and whether it’s even preferable to do so. I’ll cover this in later pieces.

Issuance

The Ethereum protocol mints new ETH every block to pay validators. It provides an additional incentive to secure the chain instead of sticking your ETH under your mattress, spending it, or using it somewhere else.

Ethereum issuance is currently stable, predictable, and low. There’s a predetermined curve which dictates how much ETH can be printed based on the active validator count. More ETH staked = more issuance, but it grows at a decreasing rate (i.e., increasing the validator count reduces the yield provided to each validator).

Source: Me

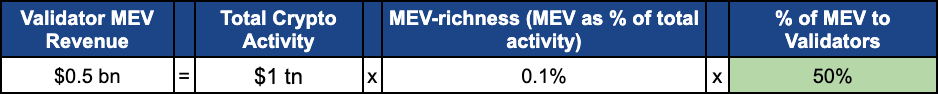

What is an Asset?

Now that we understand Ethereum’s value flows, we can reason about ETH as an asset. First, let’s define what an asset even is:

Source: “What is an Asset Class, Anyway?” Robert J. Greer, 1997, The Journal of Portfolio Management

They’re not perfectly distinct buckets – some assets display some crossover features. Still, this provides a helpful benchmark for categorizing assets.

What is a Token?

Many application tokens are pretty straightforward. Lido (LDO) is one of the clearest examples of a sustainable decentralized business model:

- Product Market Fit – The Lido protocol offers liquid staking tokens (LSTs, don’t worry I’ve got you Vance) like stETH that consumers want. Holders receive staking yield and retain liquidity without running a validator.

- Moat – Current market dynamics lend themselves to a few dominant LST providers. Do rational actors want to buy LST #1 or #10? Most go for #1 (or a couple other top ones). High liquidity, broad acceptance, and resilient security.

- Value Capture – In-demand products with returns to scale display the ability to capture value. In Lido’s example, it’s a gigantic market (staking). Lido can charge a fee for this service which accrues to LDO.

LDO controls the protocol and its associated cash flows. It displays clear properties of a “capital asset,” and traditional valuation tools (e.g., DCF) are largely appropriate.

What is ETH?

ETH is complicated – it displays properties of all three traditional asset superclasses (a Triple Point Asset, some might say). A simple DCF is clearly not sufficient in valuing it. It’s only one piece of the puzzle. I’ll give a brief explainer of each here in regards to ETH.

1. Capital Asset – Stakers & Holders Earn Income

ETH holders and stakers have a right to protocol cash flows (fees and other MEV). Stakers also receive issuance (though at the expense of unstaked holders). This displays some similarities with equities, (infinite duration) bonds, and income-producing real estate.

2. Consumable & Transformable Asset – Gas

ETH is the gas that makes the Ethereum engine run. Transaction fees must be paid to the protocol in ETH. High demand to use Ethereum → higher demand to hold and consume ETH for transactions.

3. Store of Value Asset – Monetary Premium

SoVs retain purchasing power over time and have stable demand for the underlying asset. We’re seeing very early signs of ETH as a SoV among its other use cases:

So those general frameworks make sense, but we keep hearing that ETH is “ultrasound money.” Is it possible for ETH to really grow into being “money,” and is it even a good idea? Maybe ETH is just more like a standard productive asset? This discussion will be the heart of future pieces.

But for starters:

Why Does ETH Matter?

Background in hand, we can attempt to clarify what ETH’s objective function actually is. You’ll likely get suboptimal economic policy if you don’t know what you’re even trying to optimize for.

The most coherent vision I’ve seen has been offered by Justin Drake, who gave an overview at Devcon. Crafting ETH to have “monetary premium” increases economic bandwidth and security, starting a flywheel effect:

Source: Justin Drake

Sustainability

The argument posits that blockchains are like companies, and their profit can be determined as follows:

Source: Justin Drake

Ethereum was considered “unsustainable” shortly after the Merge because it had slightly positive net issuance:

Source: Justin Drake

If Bitcoin’s capped supply makes it “sound money,” then Ethereum’s expected deflation makes it “ultrasound money.” (ETH net issuance is indeed negative since the Merge now).

Source: Justin Drake

There are two closely related variations of the above argument:

- Profit = Burn – Issuance: This only credits fees that are burned (currently just base fees, so no credit to priority fees and other MEV). “Profit” is strictly the amount of net negative issuance.

- Profit = All Fees – Issuance: This credits all revenue, whether it’s burned or not. This implies there could be some wiggle room to have net positive issuance and still be “sustainable” as long as total fees > issuance. This is the argument as presented here.

Most people seem to agree with this line of reasoning:

You even explicitly see stuff like this:

Source: Token Terminal

I strongly disagree with all of this. I’ve argued this since I started in crypto, so I’ll go on a bit of a rant (again).

For starters, PoS issuance differs from PoW in a critical way:

- PoW issuance is a direct expense to the network. The block reward is paid to miners for their work. Token holders have no rights to receive it. All BTC holders (and previously ETH holders under PoW) must eat this cost equally.

- PoS issuance is not a direct expense to the network. It’s redistribution from all holders to stakers (a subset of holders). However, all holders have equal rights to receive this cash flow*. Holders decide whether or not to stake based on their individual opportunity costs and ability to run a validator.

So I disagree on both major points:

- Fees – Issuance ≠ “Profit”

- A net inflationary network is not inherently unsustainable. If there is sufficient demand for the underlying token based on various utility and value capture mechanisms, holders may be perfectly fine with a reasonable amount of positive net issuance. The whole system doesn’t magically collapse if we guarantee that long-term net issuance is +0.0000000001%.

A net inflationary network may be unsustainable depending on many related factors. However, this black and white framing and false equivalence to corporate profitability reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the system architecture.

(Note that I am only discussing PoS issuance provided to validators. However, some other alt-L1s also issue tokens for purposes such as incentive programs. This type of issuance is more analogous to PoW issuance, or similarly a DeFi protocol that is issuing token incentives to LPs to attract liquidity. This is very different mechanically from issuing the token back to stakers of the underlying tokens themselves. Regardless, ETH is only issued to validators. Ethereum has no other issuance mechanisms.)

Better Corporate Analogy

For those of you compelled to stuff a blockchain into a corporate analogy, the below is much better (albeit they’re never perfect).

Scenario 1 – PoW Issuance

Issuance is akin to a company paying their employees in stock-based compensation (SBC). Per GAAP, this is a non-cash expense deducted from earnings (though added back to FCF which is a whole other contentious issue). This:

- Dilutes all shareholders

- Lowers profitability

Even worse, imagine the SBC is in the form of actual shares which vest immediately. This company doesn’t make much money, so they pay almost entirely in SBC. It’s also going to slowly become illegal to pay out SBC by 2140 (if we analogize to Bitcoin specifically). Every four years, you’re allowed to give out half as many shares as the year prior.

It’s been working so far:

Stock price goes up → able to pay more $ for better employees even with less shares → stock goes up more, because now they have even better employees → …

However, they’re kinda screwed unless they start making a lot of money by 2140. Hopefully they come up with a business model some time soon (Ordinals?).

Scenario 2 – PoS Issuance

This company issues new shares too, but only to existing shareholders. Every shareholder has an equal right to receive them. All you have to do is show up to vote at shareholder meetings. There’s one condition – you must bring your physical unencumbered shares to vote (yes I’m ignoring re-staking, leave me alone, it doesn’t change the logic).

You can’t be lending out your shares or borrowing against them. This issuance:

- Does not change the company’s revenue and earnings (profit)

- Does lower EPS because you dilute shareholders

This might impact your decision to buy that stock depending on factors like:

- Are you too lazy to vote?

- Is it too expensive to vote? (You must fly to the shareholder meeting and pay for accommodations, and you can’t expense the trip to the company. BNB Chain has their meeting at the Four Seasons in Vegas, Solana has theirs at a castle in Lisbon, and Ethereum has theirs at a diner in Hackensack.)

- Do you really like to lend out your shares or borrow against them?

- How many shares are being given out?

- What do you think of the company’s future prospects?

You might be ok to get diluted if:

- You think it’s a great company. You share in future price appreciation because all shares retain equal rights to future cash flows and stock issuance.

- The shares are good collateral, so people are happy to lend against it at a high LTV. You like doing this, so you derive utility value as a holder.

- They’re giving out very few shares anyway, so you don’t care that much.

Even better, imagine there’s a third-party service that will give you synthetic shares (LSTs). You give your shares to them, they vote for you, and they give you ~90% of the share issuance. Now you get most of that issuance, and you can go lend out your synthetic shares or do whatever you want with them. They’re a little less liquid and trickier to lend against, but they’re pretty good. (Re-staking also offers different but analogous benefits).

Taking the analogy to completion:

- Base fee “revenue” is immediately converted into a share “buyback”

- Priority fee/MEV “revenue” is immediately disbursed as a “dividend” of additional shares (to individual voting shareholders, randomly cycling through all of them)

- The company never builds up any reserves in its treasury

You’ll notice I also draw no distinction such as Token Terminal has between base fees, priority fees, and other MEV (they only consider base fees to be network revenue):

Source: Token Terminal

They’re all Ethereum protocol revenue inflows to be allocated however it sees fit. Whether it’s burned or sent to stakers refers to the protocol’s use of the cash, not the source.

Thought Experiment

Let’s walk through an extreme scenario to understand the logic. A PoS chain decides to offer a crazy issuance rate of 100%, so the supply doubles annually. Now the dilution is way too high even if you love their future prospects, so the unstaked holders dump the token or stake it.

100% of the token is now staked. Realize that now you can inflate it by 0%, 10%, or 100%. It doesn’t matter to their “profitability”. Everyone ends up exactly as well off in terms of network ownership and rights to cash flows.

Now that high inflation isn’t helping to further incentivize stakers, everyone decides to lower inflation to 1%. So now as an example:

- 100% of tokens staked

- $100 bn MCAP

- ~$1 bn in issuance annually

- $2 bn in fees annually

As described earlier, many would consider this network to be generating a “profit” of $1 bn dollars. But now, let’s say they change inflation back to 100%. Did the network suddenly turn into a gigantic money-burning machine that’s operating at a loss again? No, of course not. Everyone is staked, so they’re all being diluted and made whole at the same rate. Your share of the network and rights to cash flows do not change at all.

Over the course of the year, the $ price/token should roughly halve. You end up with the same MCAP, but twice as many tokens. So it was basically just a “stock split.”

PoS inflation isn’t an explicit network revenue or cost in any scenario. You just decide who to benefit:

- Increasing inflation – Directionally benefits stakers by “taxing” holders more

- Decreasing inflation – Directionally benefits holders by “taxing” holders less

However, if a $100 bn PoW chain similarly needed to increase its issuance from 1% to 100% because miners demanded a higher income, the dynamics are very different. Now all token holders are diluted because they have no rights to receive the issuance. After a year, current token-holders own half the network, and miners own the other half.

Similarly, the PoW token holders aren’t even receiving the fees (unless they’re burned). So whether the network captured $1 bn of fees or $100 bn of fees makes no direct difference to them. The miners get that money – holders have no rights to any cash flows. The only benefit is that higher fees likely allow you to keep issuance lower, because miners won’t demand such a high subsidy. So PoW token holders here “lose less money” based on fees and issuance, but they’re not gaining network share or receiving cash flows.

Staked vs. Unstaked ETH

If you want to think of it differently, imagine “staked ETH” and “unstaked ETH” are totally different assets that can trade at different prices (obviously not the case). They’re “companies” as so many of you seem to like, so the value of each is based on a DCF. Now we’ll include issuance in their DCF because they’re isolated assets.

If you increase issuance, then the “staked ETH” goes up in price based on the discounted rate of this additional future issuance. Conversely, “unstaked ETH” would go down based on the discounted rate of this additional future issuance. You’ll realize, these changes in their respective DCFs and prices then perfectly offset.

Well, guess what – there’s only one token. So, the network’s overall DCF is unchanged. Increasing the value of “staked ETH” doesn’t make a separate asset price go up. It just shifts demand on the margin from being a holder to being a staker at whatever the new market clearing rate is.

Staked ETH and unstaked ETH are the same asset. They have exact equal rights to receive future cash flows. It’s your prerogative what you want to do with it. High issuance doesn’t mean you can sell your “staked ETH” for more than my “unstaked ETH.”

Cash-flowing assets are valued based on their rights to receive cash flows. That’s why stETH and ETH trade at roughly par (in normal market circumstances). If you choose not to exercise that right, it doesn’t make your asset less valuable than another equivalent asset choosing to exercise that right. This would be like saying my stock is worth less than someone else’s because last time the company issued a dividend, I said no thanks I don’t want it.

If you want to see exactly where unstaked holders break even on purchasing power, we can measure it relative to USD for simplicity. I.e., holders want ETH/USD MCAP % increase ≥ ETH net issuance %, because then ETH/USD price stays flat. Hopefully this should be incredibly obvious.

As a simple example:

- If ETH/USD MCAP % increase > net issuance %, holders up in USD terms

- If ETH/USD MCAP % increase = net issuance %, holders flat in USD terms

- If ETH/USD MCAP % increase < net issuance %, holders down in USD terms

If the network is growing at 1% per annum in USD terms (several factors internally and externally go into this), then holders break even in USD terms with 1% net issuance per annum. Logically:

- Early networks (higher growth) can support higher net issuance while keeping holders at breakeven purchasing power (in USD terms)

- Mature networks (lower growth) can support lower net issuance while keeping holders at breakeven purchasing power (in USD terms)

But again, this breakeven is measuring dilution specific to unstaked holders’ purchasing power (in USD), not “network profitability.” In scenario 2, holders lost some purchasing power which stakers equivalently gained. It’s wealth redistribution, not wealth destruction.

Operational Costs

Something that the popular “profitability” argument also misses – physical operational costs must be accounted for. This encapsulates validator expenditure on hardware, compute cost, etc.:

This analysis is wrong. Inflation or block reward issuance is purely a fee on unstaked native tokens, or on users not participating in consensus. It’s not a “cost”. “Profit” = (network fees) – (physical cost to run the boxes) https://t.co/N1qtYOUkdZ

— toly 🇺🇸 (@aeyakovenko) March 31, 2022

Let’s do a simple example again:

- 100% of tokens staked

- 0% inflation

- $100 bn MCAP

- $2 bn inoperational costs annually for all validators

- $10 bn in fees annually

If you’re deciding from an outside perspective whether or not you want to be a validator, you have a very simple equation. Assume for simplicity that operational costs scale linearly with your stake weight (they don’t, there are some centralizing returns to scale in distributing fixed costs). For any amount of stake I put up, my income will = 10% and my operational costs will = 2%. I net 8% on my staked capital.

At a network level, the analysis here is again simple. Everyone is staked and we have no inflation, so the actual profitability to all token holders is $8 bn. The stakers collectively made $10 bn and spent $2 bn.

Looking ahead: MCAP = NPV (future fees – future physical operational costs)

Again, you could add in inflation if you like and have separate DCFs for stakers vs. holders. However, everything will net out to be the same on aggregate. The extra validator income will = the loss to holders. Similarly, if fees are burned instead of all sent to validators, you just shift the allocation from validators to other holders, but the same amount is captured on aggregate.

Thankfully, operational costs are generally relatively low for staking relative to most traditional businesses. It’s a high margin business where the predominant cost is your opportunity cost of capital staked.

So, Does Issuance Matter?

YES! A LOT!

But I think most people are wrong about why it’s important, and that clouds our ability to address it properly. Issuance is being jammed into a misguided and simplistic notion of “profitability.” A blockchain doesn’t immediately become “unprofitable” if issuance > fees or “unsustainable” with slightly positive net issuance.

There’s significant merit to arguing that ETH should be very deflationary which I’ll go into in following pieces, but it’s not for the popular reasons I presented earlier.

So, inflation is incredibly important depending on the situation/mechanics and what behavior you want to incentivize. For example, aggressive early PoW issuance was effective in broadly distributing ownership for BTC and ETH. Conversely, excessive dilution eventually becomes destructive. Relative incentivization of holding vs. staking matters a lot. Especially because you can’t just value ETH based on a DCF anyway. It’s fundamentally different from a traditional stock, and utility can potentially be derived from it in a “money-like” way.

As I mentioned earlier, would you immediately sell or stake all of your ETH if we changed the net issuance to always be 0.00000000001% forever? Of course not! You may derive utility from it as a SoV, for gas fees, because it’ll share in price appreciation, or whatever else. And inflation does impact these components of demand (which drive the real market valuation beyond a simple DCF).

As a result, changes in inflation absolutely could impact its market cap in reality. However, not in the way that most seem to think or for the popular reasons.

Issuance affects the balance of utility between unstaked and staked ETH, so we must understand it properly if we’re going to maximize the collective utility. Here’s a great article by Polynya on the pernicious effects of high issuance. I’ll also elaborate further on its potentially destructive effects in upcoming pieces.

Security & Economic Bandwidth

Broadly, the “ultrasound money” argument posits that ETH’s value is important for two reasons:

- Security – You want ETH to be worth something, and you want a sufficient amount of it staked. If Ethereum is looking for “World War III” level security to withstand even nation state attacks, then high economic security is beneficial. I generally agree here.

- Economic Bandwidth – ETH provides “economic bandwidth” for other applications. The key use cited is that of collateral for decentralized stablecoins. (I.e., if we want DAI to get really big, then we need ETH to be really big, because DAI is necessarily over-collateralized).

ETH is cited as pristine collateral primarily due to its lack of associated risks:

Source: Justin Drake

However, ETH has one problem – it’s volatile. Hence the argument that we need decentralized stablecoins to be minted against it – we want to create a less volatile asset (USD stablecoins like DAI).

This economic bandwidth argument misses some key points in my view:

- I do not believe truly decentralized stablecoins will ever meet the demand required based on current mechanisms. They’re highly capital inefficient compared to centralized alternatives, arguably more risky, and less functional. Centralized stablecoins at scale are likely inevitable. Much more on this in upcoming pieces.

- Following this, I do not believe that ETH is greatly needed for “economic bandwidth” in this context. Centralized stablecoins (and many other crypto-assets) can provide this.

- The argument is that ETH should be used to mint stablecoins because ETH is volatile. However, the best collateral shouldn’t be volatile. If we actually want to make ETH the best collateral, the focus should be reducing ETH volatility. What happens to the outstanding stablecoin supply if they’re all backed by ETH, and ETH’s price nukes? Not good.

Illiquidity Multiplier

It’s also stated that making ETH illiquid will directly make it more valuable. The argument is that the “liquid portion” should be valued based on a full DCF of Ethereum, then multiplied by the “illiquidity multiplier.” For example, if a full Ethereum DCF implies a value of $1 tn and 80% is locked as collateral or staked, then the market cap should be $5 tn.

I disagree with this line of thinking for several reasons.

- As I’ve already argued, I do not believe a DCF is a wholesome analysis of valuing ETH.

- Liquidity certainly impacts market supply and demand dynamics. If there’s less available on exchanges and you want to buy a bunch of ETH, it’ll push the price up more than if there were deeper liquidity. However, there isn’t a linear relationship here.

- Even if it was sufficient to value Ethereum exactly as a company with a DCF, you wouldn’t come up with a 5x multiple on a company valuation because you thought 80% of the stock’s holder’s haven’t recently moved their shares or they’re “diamond hands.” Being staked or “locked” as collateral ≠ “it doesn’t exist so my share of network ownership is 5x higher.” Let’s say that 80% of ETH is collateral pledged to mint stablecoins. As in my example earlier, what happens if the ETH price starts falling and those loans are under-collateralized now? Liquidations → forced sellers.

My Overall Views

I agree that economic security is valuable as described above. I’ll also note of course that economic security isn’t sufficient in isolation. Even more importantly, a network should be robust and decentralized enough to recover from such an attack, but that is a far longer argument out of scope for the discussion here.

However, as I’ve written previously:

“This security argument alone also ignores the moral argument and overall need for a robust base layer asset in this new digital world, especially with BTC’s potential shortcomings. This is an argument for another day, but an important role that I believe in and many in the crypto community clearly want as well.“

Well today is that day, which brings me to my next point. My general view is simple for all Ethereum considerations, economic or otherwise – how can the Ethereum protocol offer the greatest benefit to the world?

That goal is of course highly subjective, so now I’ll try to be a bit more concrete in how I think about this. There’s broadly two considerations as to what Ethereum can provide:

- “External” Uses – Make Ethereum a maximally flexible tool. It’s the breeding ground for permissionless innovation. Anyone can build on top of Ethereum/rollups, and they hopefully create a wide range of incredibly valuable applications. This is clearly the primary goal.

- ETH – Is ETH itself a highly valuable product for the world?

- Yes – If ETH actually stands a shot at becoming a global, un-censorable, non-sovereign, money (big if, and “money” is a vague term). I also have concerns about Bitcoin’s ability to fulfill this kind of role. If Ethereum has the best shot at building this, it shouldn’t be ignored.

- No – If ETH is just a value accretive asset that takes a margin from the activity on top of it (more analogous to some big tech stock), I would argue the answer is no.

These two goals are self-reinforcing in my view. Maximizing Ethereum ecosystem activity has several inputs which can form a virtuous cycle:

- Great Tech Stack and Social Layer – These attract activity. People aren’t likely to use Ethereum if building on it sucks, using it sucks, nothing works, and everyone hates everyone.

- ETH as “Money” – Money is arguably the largest product in and of itself. It would strengthen the social layer and attract more users if they fundamentally want the product of ETH itself.

- Maximize ETH Value – Building ETH as money is potentially the best long-term way to maximize the value of ETH. The TAM for “money” is higher than the TAM for “kind’ve like Apple stock, just DCF a ton of cash flows, but even bigger than Apple.”

- Maximize ETH Economic Security – Maximizing the value of ETH (as money) is the best way to maximize Ethereum’s economic security. (You could also incentivize a high stake percent with high issuance, but I believe this creates a cycle where the value of the asset could be negatively impacted, and it’s back to just a DCF-type asset at best, not “money”).

Conclusion

ETH is really cool, and I think it’s valuable (NFA). My goal is to better refine why it’s so cool and why it’s so valuable (still NFA). I think existing popular arguments fall short. It’s tempting to compress a nuanced topic into a couple one-liner memes, but they become detrimental in understanding how to optimize the protocol if they’re inaccurate. It’s unfortunately much more complicated.

Number go up = Demand for (economic collateral + speculation + staking [driven by MEV, pf] + store-of-value/reserve asset for the economy + unit-of-account for NFTs/ERC20s) – security budget + fee revenue – churn of speculators +/- other d/s vectors like restaking, bridging etc.

— polynya (@apolynya) February 10, 2023

And if you want to be selfish, a better argument will help you shill it better. The bankers aren’t gonna buy your bags if we say it’s ultrasound money because it’s deflationary and get profitability wrong.

Don’t worry, I’m down too.

Hopefully you now have a solid grasp of how value flows through the Ethereum protocol and why issuance is often misunderstood. Upcoming pieces will elaborate on how it can be optimized.

That conversation will be framed around what ETH as an asset is and possibly should be. This includes discussion of its place in the broader global economic and monetary backdrop, as well as the role of other crypto-assets such as LSTs and stablecoins.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are solely those of the author in their individual capacity and are not the views of DBA Crypto, LLC or its affiliates (together with its affiliates, “DBA”). The author of this report has material personal positions in ETH; stETH; Layr Labs, Inc.; and Skip Protocol Inc.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as the basis for an investment decision, and is not, and should not be assumed to be, complete. The contents herein are not to be construed as legal, business, or tax advice. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. This post does not constitute investment advice or an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to purchase any limited partner interests in any investment vehicle managed by DBA.

Certain information contained within has been obtained from third-party sources. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, DBA makes no representations about the accuracy of the information.